Exoplanets Explained: Will We Find Earth 2.0?

What are Exoplanets and will we ever find Earth 2.0?

Also Check: Why Broccolo Will Change Your 2017

Carl Sagan once said that Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena, and he wasn’t wrong. Using the most advanced equipment we have available to the world’s top scientists, we can see but a fraction of what we hypothesize is actually out there. The number of stars in our galaxy alone is mindboggling enough to make any astronomer nihilistic. Nevertheless, as our telescopes, computer systems and imaging equipment improve over time; we are beginning to understand more about what the cosmos is made of. One of the most exciting advances of our generation is the understanding of exoplanets and the realization that our planetary system isn’t the only one.

What is an exoplanet?

Simply put, an exoplanet is a planet located outside of our own Solar System. Whilst the idea of exoplanets was theorized and imagined for many years, it wasn’t until 1992 that we could actually prove that they exist. This was simply because of the enormously vast distances between our own planet and other stars. In 1992 we confirmed the discovery of an exoplanet system; a system of terrestrial-mass planets orbiting the millisecond pulsar PSR B1257+12. In my opinion, they could have given it a better name as PSR B1257+12 doesn’t necessarily roll-off-the-tongue. Since then, there has been no stopping us as we have officially located 3545 exoplanets in 2,660 planetary systems. This was accurate as of December 2016, but the number of exoplanets we find keeps growing, dramatically.

Also Check: Scotland Gets A Spaceport

Why are they so important?

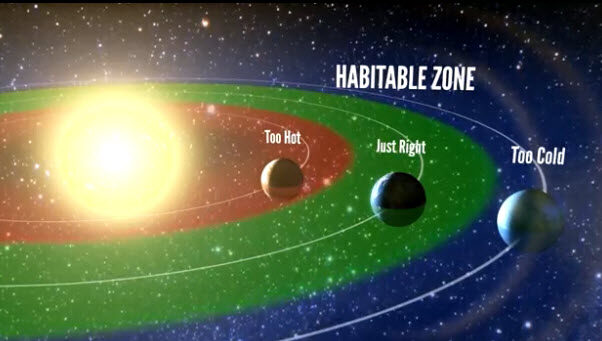

One of the most fundamentally important questions humanity has ever asked can be answered if we find the right exoplanet. Since the early civilizations began look up at the stars and planets in our own system and work out why things were spinning, we’ve always wondered whether we are alone in the universe. As our theories and technology advances through time and refinement, we can now understand more than ever before about what is needed to create and sustain life on a planet. The fundamental building block is liquid water, which relies on the planet being a certain distance from its sun. When we look for exoplanets, the really special ones are the planets that exist in a narrow band around their sun where it is an appropriate temperature for liquid water to exist. This band is called the Goldilocks zone.

How many planets exist within this Goldilocks Zone?

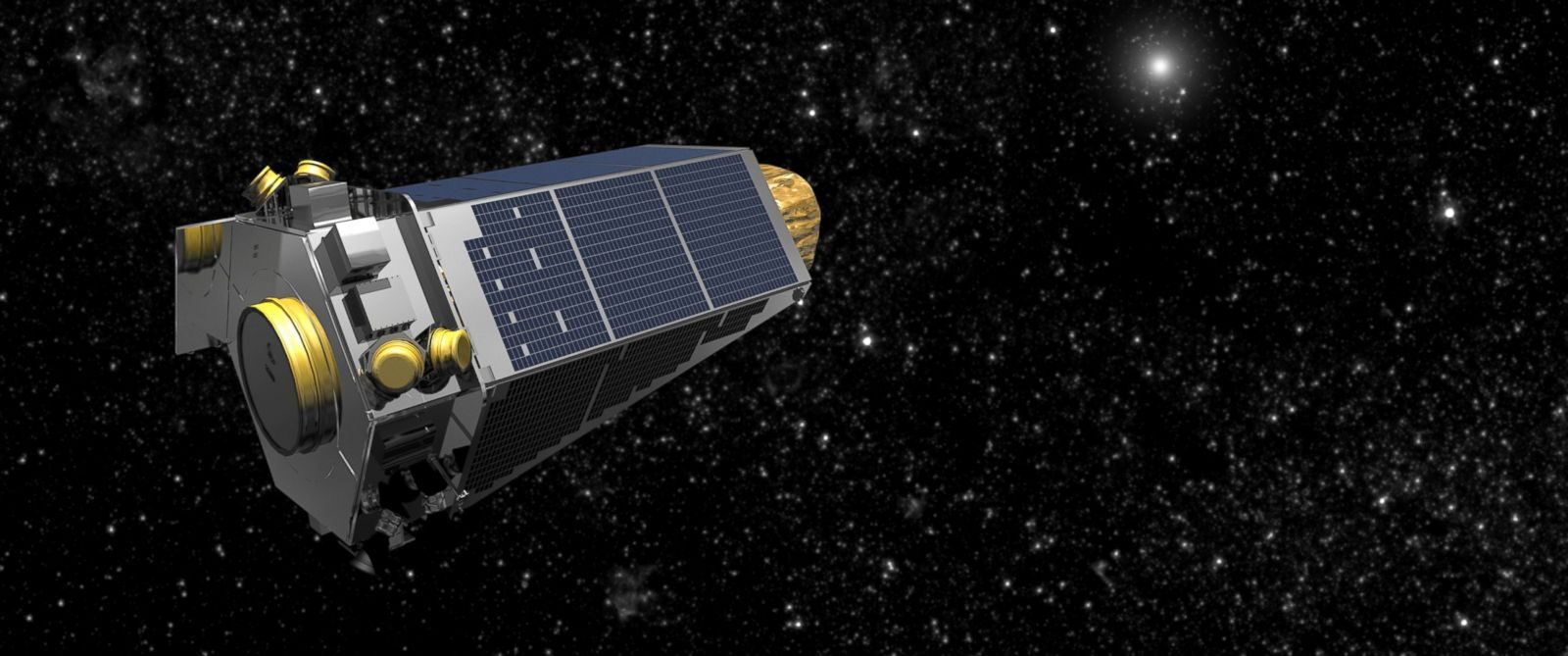

After years of research and studies, scientists used the data from space telescopes including Kepler and Hubble to estimate that within our own galaxy, the Milky Way, there could be as many as 40 billion exoplanets that exist within the Goldilocks Zone. Hubble reckons that within the entire universe, there are between 100-200 billion galaxies. You don’t even need to do the math to work out that this means there is, or was, or will be, an unimaginable number of habitable planets in the universe. I say is, or was, or will be, because the vast distance light has to travel from other galaxies to reach us means that what we see will have happened billions of years ago. Stars, planets, civilizations and even extra-terrestrial Justin Bieber’s may have happened in the meantime and the light just didn’t reach us yet.

How do we study exoplanets?

This is the tricky part. Stars that are many light-years away will appear as dots of light, even with the most powerful telescopes. Planets, even the really big ones, do not have the mass of, or the fusion that takes places in a star, and therefore are extremely difficult to spot. One of the most effective methods is called Transit Photometry, which measures the dimming effect a planet has as it passes in front of its star. Using extremely technical software can allow us to measure the mass and distance of the planet using this method. Radial Velocity is another method of catching exoplanets in action and has found the most so far. It observes the effects, even though they are tiny, that an orbiting planet has on its star. This has been the most effective with current technology, but it cannot determine the mass of an exoplanet. Microlensing is another technique that allows us to view exoplanets that are huge distances away. Microlensing is based on Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity and works on light and gravity to pinpoint star movements. The drawback here is that the sighting will only occur once. A full description of these methods can be found at The Planetary Society website.

Transit Photometry Radial Velocity

There are other methods used and most have relied on data gathered from space telescopes such as Hubble and Kepler. In the near future, the James Webb Space Telescope will be launched to hunt further into the depths than we’ve ever hunted before and it should provide us with more than a few surprises. It will be the biggest and most modern telescope ever sent into space and scientists are hoping that it will find exoplanets that are habitable.

Are exoplanets all the same?

Not in the slightest. We have found planets that take 10,000 years to orbit their star, meaning a year on the planet lasts 10,000 of our year. We have found planets that orbit their sun in just a few days and would be hot enough to melt the strongest metals in nanoseconds. We have found tidally locked planets that always face the same towards their star, meaning that one side would be scorching hot and the other in perpetual darkness. We found a planet that possibly rains glass and has 5400 mph winds which would destroy anything in its path. We found an exoplanet that could rain rubies and sapphires, and some that are made of mostly pure diamond. On the other hand, we have also found planets that we think might be suitable candidates for life to exist, or at least have existed once.

What is the nearest?

The closest exoplanet to us is Proxima b. It orbits our stellar neighbor, Proxima Centauri, and orbits its star every 11 days. This means that a year on the planet lasts only 11 days. You might think that it means the planet would be too hot to sustain life, but as Proxima Centauri is in a different stage of its life and a lot cooler than our star, the Sun, scientists think it may be capable of supporting liquid water. The problems are that the planet is very close to its star and is likely to be bombarded with different types of radiation. The other issue is that it is probably tidally locked; meaning one side of the planet always faces the star. One side will be extremely hot and the other will be extremely cold. There is a chance that the line where the dark and light sides meet could have the potential to be a habitable area, but it’s definitely a longshot compared to other places we have seen.

Will we ever visit one?

The star, Proxima Centauri, our closest neighbor, is around 4.22 light-years or 25 trillion miles. A NASA probe completed its 3 billion mile journey to Pluto in 2015 which took over 9 years. At this speed, it would take almost 55,000 years to reach Proxima Centauri. More recently, NASA’s Juno probe reached speeds of 165,000 mph but it would still take us over 17,000 years at even these speeds. A recent study and project has announced they have a way of using lasers to speed up probes and they think they can get to the system in 20-25 years. This is highly theoretical at the minute and may take some time before we start.

Personally, I think with the advances in science and engineering, it will be within my own lifetime that a probe visits an alien world outside our own solar system. Maybe not man as it would be incredibly dangerous, but definitely a probe at least, as long as we don’t destroy each other here on Earth before we have the technology needed.

Check out my Facebook page for more.